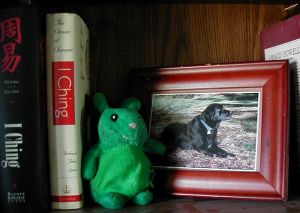

The Sacred Green Bunny

Toys and treats have distinct categories. There are the interchangable things we keep for use, like tennis balls, frisbees, dog biscuits. One's not much different from another. There are certain toys that are more fun than others. Tennis balls, for example, are fuzzy and therefore more stimulating than squash balls. Basketballs are cool, because you can't get 'em in your mouth (well, mostly).

Well, mostly....

When Crom was about a year old, I bought him a mini-basketball, tired of watching him demolish every other ball he owned. About half the size of a normal ball, and too big to let him get a tooth into it.

Yeah, right.

The second day we were playing with it, he chased it down, pushed it around a bit, worked at it for a minute and suddenly discovered that he had it in his mouth and it wouldn't come out.

He had managed to gape far enough to get it in, but at the cost of no slack to get it out. I had to puncture and deflate it to rescue him.

But face it; a ball's a ball. It would be ten years before we found a really great ball: two in fact, as different as night and day, even to a human. One fell in the category of "interesting." The other was special indeed, like the Sacred Green Bunny.

Great Balls!

The special one was the Wondrous Christmas Ball, provided by his beloved older brother and entertaining for the rest of our life. It falls in a category I discuss at the end of this essay, so for now, just a mention.

The second was a real softball — misnamed, thank you kindly — that was solid enough to endure 500 foot/pounds of curiosity, bouncy enough to provide a little action, and not fascinating enough to disassemble. We found it at Centennial Lake during our final year together. It became the walk diversion; seldom used, always worth a bit of attention. It lived in the back seat of the car, with the walk hat, the wussy spare leash, and emergency poop bags.

Crom's routine with a ball was simple. If you threw it, he'd chase it. Catch it, investigate it if necessary, maybe toss it a bit and haul it around somewhere, maybe even come back with it. But bring it back? Like, "fetch"? Really. Please think this through. If you wanted it, why did you throw it away!!?

Now the Wondrous Ball was a different story entirely than your run-of-the-mill chase item, the very antithesis of the pragmatic softball. If you shoved it around, it made a plaintive "sroonkk" noise and even jingled. Cool. It could be played with sans human. It was too solid and heavy to toss and fetch, more like a small bowling ball. And it was much venerated, of course, as a memento fraternalis. A real ball. Most of the little squishy balls they sell in pet stores? Essentially disposable, squeaky or not. And tennis balls? A bit like hardboiled eggs, but always empty. Dang.

Practical Property

Those knotted ropes supposedly good for dog teeth fall in the category of practical toys. Crom had a half dozen, including one the thickness of a ship's lanyard. They were handy for getting up a game of grab, chase and fetch, and if one went to bed bored, they were chewable with a minimum of destruction. Taken for granted, but not despised or forgotten. The step up from practical to interesting is only a slight one. The softball was an interesting toy. Not merely a usable ball, but one with character and inherent value.

Interesting Toys

The second class of toys, then, would be the "interesting." These are the toys that survive the "fifteen minute" test. This test, by the way, can be explained to you by any child, since they understand it perfectly. Some toys are interesting and exciting for the first fifteen minutes, and then whatever it was, the glamour, goes away, sometimes forever. These toys are actually variants of the least desirable toys, the uninteresting ones. It may have looked fascinating and exciting and challenging to a human (or an adult), but you know how humans are....

Hidden Toys

Another measure of Crom's sense of confidence and security was that he seldom hid favorite toys.

Being hidden is the ultimate compliment to a toy. It means the object is so wonderful that it needs to be preserved in a safe place. But it also means that the owner dog is insecure, worried that "safe places" are at a premium. Crom worried about bones, which must be stored outside; seldom about toys.

Crom would put his things "out of the way," but he didn't generally hide them in the house. Outside was a different matter, of course, where other dogs, cats, foxes, garter snakes and birds hovered constantly in the shadows, eager to filch the occasional neglected cow femur or precious toy.

It was hiding, after all, that destroyed the Holy Burrito. A lesson learned, perhaps? But no, I think Crom simply knew that inside meant safe.

There's no telling what might turn out to be an interesting toy, a keeper. Crom kept his lanyard rope for five years. Others did not survive, any more than tennis balls, but the lanyard was a constant. When he died, there was enough of it left to make it recognizable: both knots and a bit of the fray still on the ends.

A dumbbell toy in the same line as the Wondrous Christmas Ball was a practical alternative to the venerated ball. Dressed in shades of plastic green and reasonably destruction-resistant, squeaky and jingly and tough without being too hard to enjoy holding in hte mouth, it was a favored toy certain to get a moment of attention whenever I pointed it out to him. But its status was clearly lower than the ball. One among many, but not the one.

I Declare You a Toy!

Lastly (Bones, which are not toys but serious dog business, will be discussed elsewhere), there are improvised toys. When Crom was a puppy, we handled the chewing problem by giving him his own shoes. He quickly mastered the difference between his and "mine," and we never had an incident with a "wrong" shoe. When a pair of socks gave out, I would tie them together at their centers, a knot in each around the other, preferably before washing them (Dog values are dog values; get a grip), and toss them to "the kid." They were always the coolest, and generally five or six of these half-octopi were strewed around the house, for all our thirteen years.

Similarly, he inherited a pantleg from one of our girlfriends. She was making cutoffs from some jeans, and Crom sat hopefully beside the table. "You, uh, gonna throw those pantlegs away, ma'am?" Apparently not, she realized. The whole pantleg eventually, after a week of heavy use, was reduced to a hankie-sized patch that he avoided chewing, merely handling gently from time to time. I finally threw it away discreetly, four years later, the second time we moved out of state.

The Venerated

In the realm of toys one category transcends all others. The pantleg swatch achieved veneration; the woman who owned and gave it to him was one of his favorites. Her memento had status far in excess of its value or interest as a toy; it was a link to the lost, absent, and loved. These special objects picked up a name that I stuck with, when the first one emerged: sacred toys.

The first was dubbed, after a month of veneration, The Holy Rawhide Burrito of Our Lady of Las Vegas. His mom had made one of her Auntie Mame assaults on our house, filling him with joy, then gone again. She brought with her "a little present." It was a rolled-up rawhide, looking very much like a frozen burrito. Now, Crom's approach to rawhides is to regard them as potato chips, crunchy snack foods. A rawhide chip seldom lasted five minutes. A rolled rawhide might last ten.

He kept the Holy Burrito for five years, essentially undamaged. It travelled with us to Boise. He finally lost it through an accident. He buried it outside, and the damp unrolled and eventually disintegrated it.

Gifts from his big brother were venerated, none more than the Wondrous Christmas Ball. Jeof actually brought him two presents that Christmas. The other one, a giant fuzzy jack, rather like a manufactured sock-octopus, was politely accepted and ignored, never achieving any status at all. It was still in the original bag two years later.

A Necessary Story

When Crom was two, his "mom" and I separated and he stayed with her for a year before it became clear how impractical that was. I babysat him for a day and night during that time, while she was at a conference.

We hung out together and finally went to bed. I slept on the ground floor carpet, on a futon.

At the time, Crom's favorite chew treat was hard, glutinous "cow hooves." He always had one going somewhere in the house. When I woke the next morning, I found a cow hoof on the pillow beside my head. Beloved.

The ball, however, became a favorite possession immediately. Crom would go looking for it and bring it to his bed in the evenings. If it turned up where it didn't belong (i.e., I had moved it in some conspicuous and inappropriate way), he would take it back to its proper location. If I bumped it, he would chase it, knock it about a little. It occupied a place in his life similar to mine (and to his in mine) — taken for granted and instantly missed — necessary and expected as an eye.

My own contribution to the venerated possessions was the Sacred Green Bunny. Pulled from a sale bin at a pet store, it was a green fabric bunny about six inches tall, filled with fake beans and a squeaker. Again, Crom's general routine with squeaky animals was to disassemble them. A fabric frisbee, covered in fake fleece, had its squeaker removed in five minutes, then lasted months as a silent toy. Likewise a fuzzy lamb that squeaked only briefly and soon was gone. Generally the removal of the squeaker had the side effect of demolishing the toy, so I never bought expensive things.

But the Sacred Green Bunny was another matter entirely. He was so taken with it that the next day I went back to the sale bin and got another. It was the ultimate toy, apparently, capable of distracting from anything else, irreplaceable.  And fragile beyond his affections. He punched a slight hole in its chest, where a heart would be pinned, and when I gave him the other one, putting the first away, an identical hole in that. It was a possession I retained custody of, monitoring its condition and putting it away when loving destruction seemed imminent. If he wasn't through with it, then a bit of prestidigitation was called for to swap for the twin.

And fragile beyond his affections. He punched a slight hole in its chest, where a heart would be pinned, and when I gave him the other one, putting the first away, an identical hole in that. It was a possession I retained custody of, monitoring its condition and putting it away when loving destruction seemed imminent. If he wasn't through with it, then a bit of prestidigitation was called for to swap for the twin.

It lived with us, its secret twin known only to me, for more years than I can recollect. When it appeared again, the world focussed upon it. When it was time to put it away, we always had to do something else entertaining, to make up for the loss. He played with it as gently as he could, like Koko with her beloved All Ball. Had I buried him, I would have wanted to bury it with him. Because it lived in secret places, I didn't think of it or run across it when I cleared the useless debris from the house after Crom was gone. And then, a week later, I found it, the two of them with their twin leakage in their twin chests.

It was bad, that moment. And I could not discard them. I kept them. Just as I kept the lanyard rope and the Wondrous Ball, my own mementi fraternalis, tokens of loss, not memory. Memory needs no tokens.

Contents

- In Memoriam: Crom — Introduction

- Our First Years: Sharing Education

- Dog Humor: By, and About

- The Sacred Bunny: Regarding Toys

- Crom's Death: A Sudden Nightmare, March 23, 2004

- Cautery: Finding Link

- Link's Walk: Some Dog-Walking Tips

- Next Year: March 23, 2005

- Dog Wits and Bird Brains — Essays on Animal Intelligences

- Crom's Own Pages — A Tribute to True Love

- Table of Contents — Dogs and Other Creatures